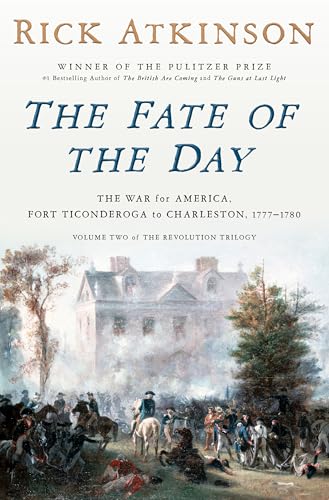

The Fate of the Day

The second book of the Revolutions trilogy is a rarity for me. I actually read the first book early enough to be eagerly anticipating the release of the second.

The second book of the Revolutions trilogy is a rarity for me. I actually read the first book early enough to be eagerly anticipating the release of the second.

In general, it has lived up to the anticipation. It does give me some feel of disjointedness, compared to the first book. The secondary reason for that is probably just my own memory of the first book cutting things out to make more sense of it.

The primary reason is of course that the war continues to expand. More people and more places are continually being drawn in, pulling you ever farther away from the nominal centers of gravity of Washington and the Continental Army, and the two Howes.

We start at one of those far-distant places on the fringe of events: France. The curtain rises on the court of Versailles, then moves over to Benjamin Franklin, ensconced in Paris, making a memorable impression, and helping slowly convince France that the war in America is worth intervening in, lastly, we go to Bordeaux, where an excitable young Lafayette is preparing to join the war personally.

French, and Spanish, involvement in the revolution is a continuing thread through the entire book. But, the full scope of this isn’t explored, only what is directly pertinent. We get a one-sentence notice of the loss of all French holdings in India. But there is more on the various campaigns going down into the Caribbean, and a bit on Spain’s desire to get a couple of treasure fleets in before risking any sort of action, and their desire to regain certain territories… which would turn into a problem later. Now, it’s more a passing mention.

The main action starts up at Ticonderoga, the fort successfully taken and held by the Continentals earlier. Now, there’s a new British army coming down from Canada, and the defenses are woefully ill-prepared. Compared to the desperate struggle a year ago, Fort Ticonderoga falls easily. The way is open to go down the Hudson River and join up with the forces already in New York.

This does not happen, for reasons given in almost any history of the war, as it’s one of the critical points of the war. Burgoyne is now at the end of a very long supply chain, and help is not coming from the south, as Howe is off in Pennsylvania, driving the rebels away from their capital of Philadelphia. The reasons for this… are hard to understand, since a link up was approved as part of the plan in advance, but so was the offensive out of New England, and no one seemed to really think about the fact that the two goals were at odds with each other.

Germain’s success turns into one of the two real rebel successes in this volume, with his side operations being beaten back, and then his stalled army finding itself sieged and forced to surrender. The other success is getting France to join in; overall even more significant, even if the immediate effects look like a number of missed opportunities and failed naval operations. The fact is that Britain now had to protect itself on both sides of the Atlantic, seriously hampering its naval position, and worry about the various sugar islands in the Caribbean, spreading troops afield just when they need to be concentrated in the colonies.

Covering from 1777 to 1780, the later parts of the book cover the switch to “Southern Strategy” by the British. With every move in the northern colonies stymied by Washington’s army, it is one of the few ways to conduct an offensive, especially with the shortage of troops with which to conduct an offensive. I’m used to hearing about the fall of Charleston (which is the end of this book) as the opening of the Southern Strategy, but here we get to see the seizure of Savannah the year previous. D’Estaing tries to retake it, but that is one of the missed opportunities. The real point is that taking Savannah is nearly synonymous with taking Georgia as a whole, and Charleston/South Carolina is just rolling up from that flank, and Washington’s army is a long ways away. Now, if the British can just get the Loyalists armed and organized, and pointed in the right direction….

Outside the military plans, maneuvers, successes, failures, and many excellently described battles, we also get to see the Continental Army start to turn into a real organization. Money is an ever-mounting problem, and that is gone into as well. But we see a disastrous supply situation at Valley Forge get reformed, and the troops start getting drilled. Both of these are because of characters who are generally remembered today, at least by any Revolutionary War buff, and Atkins does well with them, and everyone else he touches.

There is more than a bit of “middle book syndrome” going on here. It is nicely bookended by events with major repercussions, and plenty of importance happens in between. But the book does feel like it doesn’t quite gel into a whole. As mentioned at the beginning, that’s because the scope has widened, and while Atkinson is successfully keeping a lot of balls in the air, there’s a lot of balls to keep track of. Still, it’s an enjoyable read, and recommended to get more detail on a period of military stalemate.

Discussion ¬