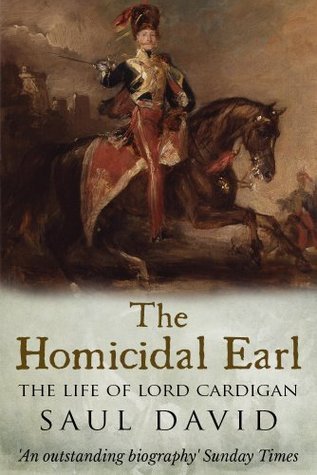

The Homicidal Earl

James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan’s, name is best remembered with the cardigan sweater.

James Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan’s, name is best remembered with the cardigan sweater.

The person will forever be known as the man who led the Charge of the Light Brigade.

At the time, he was already well known, as he had been involved in a number of scandals and political fights in the public arena, and a few duels got him the nickname of “the homicidal earl”. History has not been too kind to him, and Saul David’s book is looking to correct this, and has important things to say.

But, at the same time, I think he’s much to fast to let some problems go. The start of Cardigan’s career was spent as colonel of the 15th Hussars (after buying several promotions), and is there that the problems start. Trying to have a unit in a high state of drill in the quickest manner possible, the unit was put through a grueling schedule which wore out the horses and ended with a court martial of one of his captains, and was so disastrous that Brudenell (not yet an Earl) was removed from command, and his name gained a negative notoriety.

Two years later, his dismissal was reversed, and he was put in command of the 11th Light Hussars. At the time he took charge, they were just being rotated home after duty in India. Cardigan was not exactly swift in going out to take command, finally arriving shortly before the transfer to Britain. This time, there were a series of public disputes with various officers. The end result was a well-trained regiment, which David obliquely points up. However, a better leader would have managed this without a continual parade of arrests and disputes and court martials of his own officers, and Cardigan bears all the blame for making sure this would happen. When he first took command, he made clear he thought little of “Indian officers” (which are British officers who served in India; I do not care to think of what he’d have to say about actual native officers).

The general motive behind this is that commissions to units serving outside of Britain were cheaper, and therefore anyone holding such was a social inferior. Since the other officers were gentlemen who were unused to being snubbed. It also supported an instant break in the officers between antagonistic pro- and con-Cardigan camps. Any leader worth having does not do this.

In comparison, his record in the Crimea War is actually quite reasonable. Well, other than his constant fighting with his superior officer, Lord Lucan, a brother-in-law who he detested. Given past history, the two could have done much worse, and the orders that led to the famous Charge were more than incoherent enough to lead to disaster if passed between people who liked each other. That said, he had opportunity and initiative enough to find a better course than charging down the valley at what he supposed the objective must be. Worse, once there, he seems to have expected that’s where his part ended, and did nothing to bring order out of the chaos that inevitably resulted as the Light Brigade got past the Russian guns.

David does point out some good correctives. Cardigan has often been seen as a dunce, and it’s fairly evident he was smart enough, but did not have the upbringing to curb an excitable temper, nor to consider anyone’s needs or views other than purely his own. He, and much of the upper command levels of the British force in Crimea, had little cause for being responsible for so many with so little understanding of anything beyond prestige.

My copy of the ebook (which seems to have been superseded) has plenty of minor problems. Words broken in the middle (formerly broken between lines, no doubt), occasional mistaken characters (‘l’ for ‘1’, etc). This follows the common pattern of getting slowly more common until about 3/4 of the way through the book, and then clearing up again for the end. But there’s no big problems, and no formatting goofs, so it’s still a very readable, if not entirely cleaned up text. The current version (with the same cover) may be better.

Discussion ¬